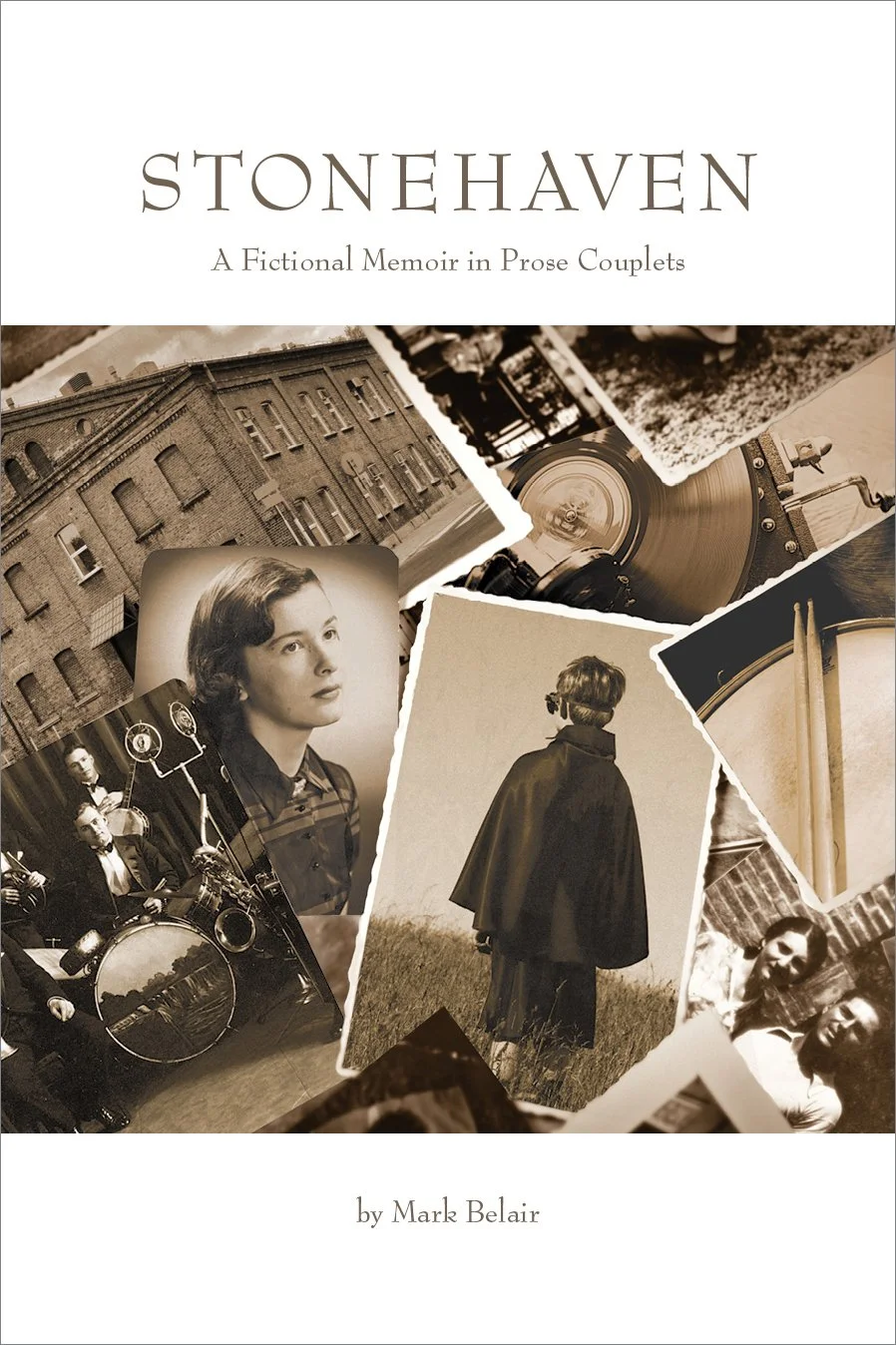

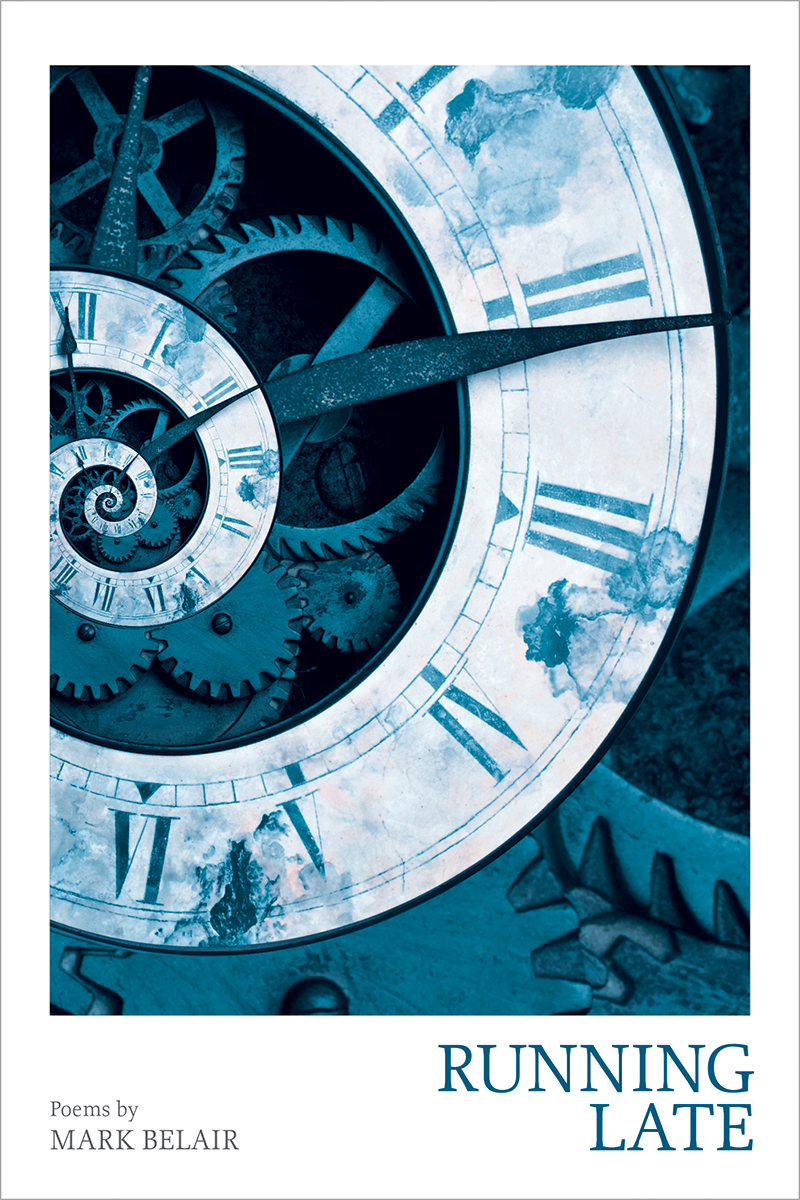

Stonehaven: A Fictional Memoir in Prose Couplets

By Writers Room Member Mark Belair

Stonehaven, a book-length project by Mark Belair, describes itself as, “A fictional memoir in prose couplets”—a unique form for a narrative that is itself intensely original. This work uses the conventions of poetry and the conventions of memoir in equal measure to create something blended, strange, and utterly absorbing […] As in life, there are no neat conclusions here, but instead a gradual process of growth which the author captures with stunning acuity. – Neon Books

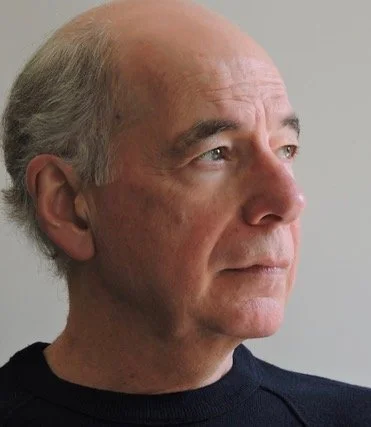

Bio

Mark Belair’s poems have appeared in numerous journals, including Alabama Literary Review, Euphony Journal, Harvard Review, and Michigan Quarterly Review. Author of seven collections of poems, his most recent book is Stonehaven, a work of fiction (Turning Point Books, 2020). He has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize multiple times, as well as for a Best of the Net Award.

Also a drummer and percussionist, Mark is a graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, where he studied in both the jazz and classical departments. In the course of his career, based in New York City, he has pursued both those musical tracks.

He has recorded with jazz greats Bill Evans (Living Time) and Joe Lovano (the Grammy Award-nominated Rush Hour on 23rd Street) as well as performed and recorded with Gunther Schuller’s New England Ragtime Ensemble (including the Grammy Award-winning Red Back Book of Rags) and Mr. Schuller’s Mingus Epitaph band.

As a classical musician, he has performed with the New York Philharmonic and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The many conductors he has worked with include Leonard Bernstein, Seiji Ozawa, and Eugene Ormandy. He also performed as a guest artist with the Bruckner Orchestra in Linz, Austria.

His versatility has made him in demand for show work. He spent twelve years as the percussionist with the hit Broadway show Les Miserables and, before that, four years as the drummer with the original Off-Broadway production of Little Shop of Horrors.

With the New England Ragtime Ensemble he has done extensive touring in the US, Europe and Russia. He has performed with them at the White House, on PBS’s “Live at Wolf Trap” and on Garrison Keillor’s Prairie Home Companion.

As a student, he attended the School of Orchestral Studies at Saratoga Springs, where he studied with Charles Owen and Jerry Carlyss of the Philadelphia Orchestra. At the New England Conservatory of Music, and for two summers at the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood, he studied with Vic Firth of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. At Tanglewood he received the C.D. Jackson Award.

A reading from Stonehaven:

Executive Director Donna Brodie in conversation with Mark Belair:

Q: Since The Writers Room is a workplace, tell us about your workplace habits.

A: Through trial and error, I have found that certain writing routines work for me. Writing at home holds too much promise of distraction, but once I enter The Writers Room and sit at an empty desk I get the cue: it’s time to focus and work.

I always have a number of poems in progress, and the Room is where I stress test them at a snail’s pace. To further slow things down, I handwrite each poem I’m working on at least once a week. That downshifting from the pace of a laptop alerts me to lines that, though I thought them set, can still be improved. To slow things down even further, once a poem is finished, I file it away. Then every two years I review my stash.

At that point, the work is cold to me. I read a title and have no idea what’s to follow. And though every poem I filed away seemed perfect at the time, they all need further revision. I find some passages underwritten, some overwritten. This final revision is where I have the distance and perspective to find a poem’s own best balance.

Q: You mention working on poems in progress. Where and how do they start?

A: Almost never sitting at the desk. For me, a poem begins when something happens that I sense is meaningful but don’t know how so. That can happen anywhere at any time, prompted by events large or small. So I begin to describe the surface incident in order to be led, by the unfolding poem, to the buried meaning I’d sensed. In a way, I write a poem to find out why I needed to start it.

Q: You’re also a musician. How do drumming and poetry relate to you?

A: Well, of course, in the rhythm, stresses, pauses; the groove- forward-leaning or relaxed- a drummer provides for a piece of music what a poet must provide for a poem. Also, for me, music is a collaborative enterprise and there is nothing better than working with your fellow players to create something that none of us, individually, would have come up with.

Poetry, by contrast, is a solitary pursuit with a highly individualized result.

I feel my own best balance when I can do both.